New York has an old tradition of nurturing see-and-be-seen restaurants. A mysterious recipe of timing, personality, hucksterism, atmosphere and location built legends like Luchows, Serendipity, Elaine’s, Le Cirque and the Russian Tea Room.

Today, thousands of restaurants crowd the tiny island of Manhattan vying for clientele and buzz. But in the late 19th century, there was room for more as a hungry horde of nouveau riche clamored for good society and good food, in that order.

Seafood and Seeing Stars

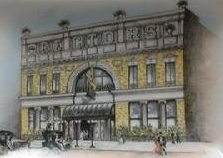

The timing was right for Charles Rector, who had already launched a successful seafood restaurant in Chicago in 1884. He opened a second Rector’s in New York City in 1899, a time of high living and big spenders. The Gay Nineties society of financiers, singers, dancers, actors and gamblers included men with fat rolls of money in their pockets who strutted around, tipped lavishly and put on a big show. They were-self made millionaires without manners. Their goal was to be seen and Rector’s on Broadway, in the heart of the theater district, quickly became the place to do it.

Noisy and ostentatious, night after night, they streamed through the revolving door (which was the first in New York)—some celebrating personal triumphs, some trading rumors about scandals. Actresses paused for applause, chorus girls hung on the arm of older patrons hoping for a diamond trinket from the jewelry store next door after the lobster and champagne dinner. (The store stayed opened late into the night.)  The Ziegfield follies captured the spirit with a hit song If the Tables at Rector’s Could Talk, and Paul Potter, the playwright, titled his translation of a French farce The Girl From Rector’s.

The Ziegfield follies captured the spirit with a hit song If the Tables at Rector’s Could Talk, and Paul Potter, the playwright, titled his translation of a French farce The Girl From Rector’s.

One of the notorious new society and a regular patron was Diamond Jim Brady. Because of his legendary appetite, the restaurants competed for his patronage. The menu for his before theater dinner began with three dozen oysters, followed by a dozen hard shelled crabs, then six fresh lobsters (a Rector’s specialty) a steak, and for dessert—pastries—not one or two, but the entire contents of the tray. Along with the food, he drank carafe after carafe of orange juice—he did not drink intoxicating beverages.

What About the Food?

Although Rector’s had the reputation as a “court of triviality,” Charles Rector took his food service seriously. He had already established the Rector reputation in Chicago as the place for fresh seafood and he wanted to compete with the best in New York, like Delmonico’s and Louis Sherry. So, when Diamond Jim Brady, who had enjoyed filet de sole Marguery in Paris, mentioned that he might want to change restaurants if Rector’s did not come up with something just as delicious, Charles took action. He did not want to lose an important patron.

He turned to his son George, who was a third year law student at Cornell University, and sent him to Paris to learn how to make the sauce. This was no easy task even though George already had some experience as a chef in Rector’s kitchen in Chicago. The chef at the Café de Marguery in Paris was not about to share his recipe for the sauce. So George did the next best thing—he applied for a job as a bus boy at the restaurant and gradually worked his way up through the ranks of waiter and apprentice cook until he gained the trust of the chef. This didn’t happen over night. In fact, it took a year, but finally, after trying for fifteen hours a day for two months, he learned to make the sauce to the satisfaction of a jury of seven master chefs and realized his real goal—he had mastered the recipe for Sauce Marguery.

That was the beginning of a very successful career for George Rector as a nationally and internationally recognized chef. Over the years, George created many dishes for his patrons and always added “a la Rector” to the important ones.

A La Rector

Rector’s fed 1,000 people a day at an average cost of two dollars for dinner. The cost of lunch ranged from thirty-five cents to fifty cents. The waiters were polite and stayed on year after year. They wore full evening dress and were not allowed to wear glasses or a white vest. Furthermore, they must shave cleanly every day and were required to wear full dress shirts. If they were caught straying from these rules, they were suspended for ten days.

It wasn’t just the food and service that fascinated the guests. So did the tableware. The linens were imported from Belfast with the famous Rector griffin interwoven in the fabric. The silverware was made to order by American silversmiths, stenciled with the griffin. Souvenir hunters took about 2,000 pieces a year. If a patron asked for a spoon or knife, Rector’s gladly gave it to him, but if a patron were seen stuffing silverware into his or her pockets, Rector’s quietly added the cost to the dinner check. The most they ever charged was $78.

Rectors, Tarnished

In 1911, based on their success, Charles Rector built a magnificent 14-floor hotel with a restaurant on the first floor. But, alas, its success was short lived. The Girl From Rector’s, that naughty French farce advertised everywhere as ”a spicy salad with very little dressing” betrayed the very name from which her title had been launched. It gave the impression that Rector’s was a risqué hotel and clients stayed away.

Even though good friends like George H. Cohan rented a suite of rooms for a year, the hotel went bankrupt in two years. The reputation of Rector’s had been doomed by a girl who never even existed.

Brokenhearted, Charles retired. George leased the name of Rector’s and spent the next five years in partnership with others, but the business had changed. Dining out was no longer an art. Instead there was a new craze for dinner joints where you could dance the turkey trot, fish walk and bunny hug to loud music.

Early Mobile Dining

George finally retired and moved to the suburbs, but continued his career as a chef. Then in 1928, the Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul & Pacific Railroad retained him as Director of Dining Car Cuisine. The railroad claimed him as “the most distinguished man in the world in his particular endeavor” and passengers were assured that every week Mr. Rector would place some of his choicest preparations on the regular menu. George put a positive spin on this by proclaiming that although the original Rector’s was closed, they were now open for business inside the dining cars of the Railroad.

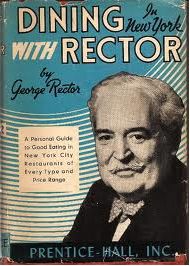

George left this endeavor in 1930 but still continued his interest in food. He traveled extensively and wrote regularly about regional foods for The Saturday Evening Post and in 1937 he played himself in the movie Every Day’s a Holiday starring Mae West. He had a regular spot on CBS radio called “Dine with George Rector” and wrote a book called “Dining in New York with Rector.” Here are some of his recipes.

Rector’s is long gone but in many ways it was a foreshadowing of the role restaurants continue to play in the dance of “see and be seen.” Remember that the next time you bump into Di Caprio at Tribeca Bar and Grill, you are continuing a long and enduring tradition.

Great post! If you mention the name Rector’s today in New York City, almost everyone would shrug their shoulders and give you a blank stare. As you say, 100 years ago maybe one of the most famous restaurants and restauranteur’s in the world, let alone New York, today completely forgotten.

You’ve done a very good job at relaying how popular and well known Rector’s once was and demonstrating that fame and popularity are merely transitory.

Hi B.P.

Restaurants have a way of burning brightly and then vanishing. Perhaps a cautionary tale for all restaurateurs, no matter how many months it takes to get a reservation with them at the moment.

i have a 16×20 photo in great condition i bought at an antique shop. The photo is of the inside of Rectors. It is at a anniversary party of mr & mrs b w loucheed.Oct 9 1917 the table is dressed in a form of a navy ship and all of the members of the earl fuller band are at the table along with others that i would love to identify.

What a lovely discussion on the history of The Rectors! I’ve baked a cake from George Rector’s “Cook’s Tour With George Rector” syndicated column 1943 called Labor Saving Cake and I’m about to post it, so I very much enjoyed landing on more history of these fascinating food men. I’ve included a link to this article in my blog post.

I have an original hand painted Rectors Menu from1913. The address on the menu is 48th and Broadway

I had a Swedish cousin who worked there circa 1918. Later worked at the Waldorf.

I had been reading a book which mentioned Rector’s restaurant to be on 44th & Broadway. I had worked in that area for years. Would love to know what building now stands on the site of Rectors. I did notice in a previous message the menu said 48th st. Does anyone know what the exact location was.

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/1500_Broadway This was where it was located now. Was the hotel cartlidge till 1972 then building demolished and this was built.

My Grandpa worked at Rector’s in the 40’s and 50’s, well, not sure of the years. He was guy who sat the people down for dinner. I still have steak plates from the restaurant.