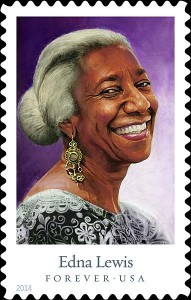

Several months ago the US Postal Service released a five-stamp series honoring trailblazing chefs; the beatified included James Beard, Julia Child, Joyce Chen, Edna Lewis, and Felipe Rojas-Lombardi. Alas, this comes too late in our history to provide what would have been a literally delicious irony—since stamps are now self-adhesive, we no longer need to lick them, and thus have lost the chance to taste the gustatory giants themselves (not to mention the critical appraisals that might have followed: “Edna Lewis leaves a sheen of mint on the tongue”).

Several months ago the US Postal Service released a five-stamp series honoring trailblazing chefs; the beatified included James Beard, Julia Child, Joyce Chen, Edna Lewis, and Felipe Rojas-Lombardi. Alas, this comes too late in our history to provide what would have been a literally delicious irony—since stamps are now self-adhesive, we no longer need to lick them, and thus have lost the chance to taste the gustatory giants themselves (not to mention the critical appraisals that might have followed: “Edna Lewis leaves a sheen of mint on the tongue”).

What the new series does provide, however, is an opportunity to consider the phenomenon of celebrity chefs itself. As a signifier of national fame, the postal service is more the last lap than the initial nod; by the time your mug makes it to a stamp, you’ve already dyed yourself pretty deeply into the cultural fabric. So the fact that these five icons are now smiling out at us from the covers of our electric bills is a pretty clear indication that they’re already comfortably—and permanently—settled in our national pantheon.

Which raises the question: how do chefs, of all people, manage that? It’s an easy call when it comes to athletes, actors, musicians, and fashion designers; their work is accessible not only by multitudes, but pretty much in perpetuity. Miles Davis might play a club date in 1957 to 30 people, but you can still hear it today on Spotify. Similarly, your coffee mug may well have Andy Warhol’s Marilyn on it. Thanks to technology, the visual, literary, and performing arts aren’t bound by considerations of immediacy and impermanence.

Tasting a Phenomenon

The culinary arts, however, are. Our eyes and ears might be able to appreciate an artist’s work across oceans and decades, but our tongues are pretty much limited to the here and now. Julia Child’s boeuf bourguignon might be a masterpiece on par with Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, but we have to take that on faith, because we can only directly experience the latter.

These chefs did no less than redefine what it means to be human; in the late 20th century, as regulation, mechanization, and industrialization reshaped our lives, they brought us back to to the garden and cooled our fevered brows. They reminded us that to eat well is to live well, and then they showed us how to do both.

Or can we? You might make the argument that Child’s recipe for boeuf bourguignon (from her seminal text, Mastering the Art of French Cooking, Volume 1) is like the score Mozart left behind for his Jupiter symphony. In each case, the masterpiece isn’t the collection of pages itself; it’s what the disciple creates by following the instructions laid out there.

Even so, the endeavor requires a commitment of time, energy, and faith, with no guarantee that what we produce from Child’s recipe will be entirely representative of Child herself (kitchen techniques being as idiosyncratic as any other form of self-expression.) And even if Child’s recipe were reproducible, it’s not mass producible, so that your stunning boeuf bourguignon à la Julia is limited to your dinner guests—as opposed to the multitudes hearing the Jupiter on Live from Lincoln Center.

Louisa Chu, Sam Toia, Stephen Chen, Pritha Mehra, Stephanie Izard, Ruth Louis Smith, Yvon Ros, Monica Eng unveil the U.S. Postal Service Celebrity Chefs Forever Stamps on September 26, 2014 in Chicago, Illinois. (Photo by Tasos Katopodis/Getty Images) (PRNewsFoto/United States Postal Service)

So what, then, explains the continuing fascination with high-profile chefs? The USPS defends their choice thusly: “…they invited us to feast on regional and international flavors and were early but ardent champions of trends that many foodies now take for granted. As they shared their know-how, they encouraged us to undertake our own culinary adventures.” There’s a kernel of truth there, but it’s too blandly understated; it makes the chefs seem no more than lifestyle coaches.

In fact, what these chefs did was take one of the primal human needs—to eat—and reintroduce, after decades of austerity and guilt, a sense of joy to it. They taught Americans not to view their kitchens as work stations, but as creative studios—places to be bold, to think big, to embrace discovery. Their contribution to American lives is similar to that of their near-contemporaries Masters and Johnson, who demystified that other room in the house, banishing shame and secrecy in favor of playfulness and pleasure. In short, these chefs did no less than redefine what it means to be human; in the late 20th century, as regulation, mechanization, and industrialization reshaped our lives, they brought us back to to the garden and cooled our fevered brows. They reminded us that to eat well is to live well, and then they showed us how to do both.

Considering which, it’s rather amazing the USPS took so long to honor them. Never mind; let’s consider it the public-relations equivalent to slow cooking, and raise a glass to them all the same.

Leave a Reply