“I’m debating: roast duck or pork bun.”

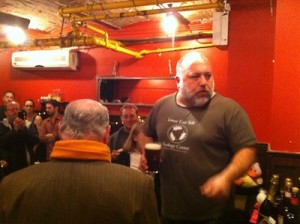

Chef Jimmy Carbone hosted a Duck-Off recipe judging contest on a recent Saturday afternoon. All (yes, all) proceeds went to Food Systems Network of NYC.

Jimmy Carbone says this to me over the phone as he makes his way through Chinatown. He just left his young daughter’s soccer game—urban kids’ play near the Manhattan Bridge—and is walking to his utterly excellent subterranean eatery and (for lack of a better term) bar — Jimmy’s No. 43. It’s here, steps down off 7th Street in the East Village, where you can find one of the best curated beer lists in the city; where you can fork into an unfussy but perfect plate of pork belly with wilted escarole and locally farmed polenta (and other inspiring dishes that won Jimmy’s a Snail of Approval nod from Slow Food NYC); and where you can drink a glass of often-overlooked Muscadet from the Loire or dry and disarming sparkling apple mead from upstate New York.

I’m about to tell him to pick the pork bun, but I should know better than that. Before I get the words out of my mouth, he blurts his choice:

“Roast duck! Yeah, that’s what I want.”

The week before, Carbone asked me to be one of the judges at his first Duck-Off, a friendly, Saturday-afternoon cooking competition where a mix of eight professional and home cooks let the feathers fly to see who was the best duck chef in all of Gothamland.

Tickets were sold at 20 bucks a pop to about 150 hungry, quack-crazy eaters who got to sample as much of the competing dishes as they liked, with all the proceeds going to Food Systems Network of New York City, a not-for-profit dedicated to ensuring the health and well-being of New Yorkers through access to nutritious and safe food, and to supporting a strong, sustainable regional farm and food economy.

But this is entirely Carbone’s M.O., and not the first Saturday afternoon fundraiser he’s hosted to feed those with cash for tickets and give it to feed others who don’t; a sort of duck-leg-wielding Robin Hood for the modern day.

A Man Who Found a Plan

Going by outward appearances, Carbone is the kind of guy you might not be able to peg right off the bat. Barrel-chested and bearded, he could be an extremely effective and intimidating bouncer whose mere physicality could keep the peace. But Carbone? He’s a lover—of great, simple meals; of people; of family; of social justice—not a fighter. Or, at least, one who chooses to thrust and parry with kitchen ingredients instead of a sword.

“My father’s family was from Genoa. My father’s grandmother died, so his mother was trained in a convent outside of Genoa ‘til she was 16, where she learned all the old culinary arts, like baking crusts and tarts and meringues.

“My mother’s side came over in the 1900s to a shoe factory town in Massachusetts. They worked in the factories, but my grandfather was a country man. He gathered mushrooms and made his own sausage. In fact, he had his own kitchen in the basement which was for his food—the dirty stuff like butchering and making sausage. My grandma had the regular kitchen, where she would make the pasta and the dinners.”

For Carbone, this intense, old-world influence (or, at least in the beginning, a desire to have great food around when he wanted it) would be the thing that eventually directed him to take over a former Ukrainian social club, which happened to have a decent kitchen, on a handshake and a prayer. Despite the rough and tumble business that owning a restaurant is, to him the whole idea of it simply felt very, very natural. “That’s what we did in my family. There were always people around, and there was always food. I didn’t realize how important that was until I left home.”

So the story goes, he went away to college and–as many young, well-fed offspring do once they set out into the wilds of canned cafeteria hash and congealed, midnight pizza–found himself a little bit lost. “This is a dumb story, but… I didn’t really know how to get food! All my life, I had all this great food available to me, but once I was away from that, I just kind of froze up.”

Restless and hungry for more than what was on his plate in all forms in the world of higher education, he dropped out to travel, heading to Europe and eventually hitchhiking his way to Turkey and Iran. “I went with truck drivers one way and local buses back. I played guitar in Munich. I was so naïve.” But one of the things he re-discovered on that independent trek was a love of simple food, and a burning desire to spend the rest of his life forming some kind of connection to it.

After kicking around and trying on the life of a thumbs-out troubadour, eventually he returned to the States, landing in New York to work in myriad kitchens and take a course with the Sommelier Society of America. “I was never attracted to fine wine, but I was attracted to really good value country wine. It’s why I like beer, too.”

Carbone did all the cooking at first, but only does it in a pinch these days, relinquishing the stove to current chef, Richard Pinto—who also tossed his toque in the ring at the Duck-Off, making an outstanding, velvety duck rillette that, were it not for a charity, I might’ve heisted when no one was looking.

Ducking Our Responsibility

I was introduced to Carbone about a year or so ago, when writing a story about a sparkling apple mead maker for Edible Manhattan. A few months later, he asked if I’d like to judge a pie contest at the restaurant benefiting the Youth Farm at the High School for Public Service in Crown Heights, Brooklyn.

The school teaches kids not just about healthy food, but how to grow it themselves, and provides those veggies and fruits to the high school’s cafeteria and surrounding community.

I’d never heard of it before, but that’s what Carbone has become very good at. New York is full of celeb-u charity events and well-supported causes; but there’s a whole universe of smaller and no less relevant food-related issues to put your weight behind in this city of nearly 9 million. It wasn’t just an afternoon day of eating pie; it was eye-opening.

When I met the other judges—a restaurateur I knew, another journalist or two, a pastry chef, all of us varied in ages and levels of shyness or boldness and occupations in the industry—I was kind of amazed at the people he collected to come on down on a Saturday.

Same for the Duck-Off. Chefs especially don’t get a ton of free time, and to get several to give up precious Saturday afternoon hours before slogging away in the kitchen at night? It was pretty cool, and all part of Carbone’s ultimate vision sparked by, among other things, a fundraiser gone wrong.

All Expenses Spared

“When we first opened, someone came to us who we didn’t know that well to do a chili cook-off for charity. Afterward I realized all the money they raised, they basically spent—they hired a band and a sound system. So they didn’t really raise any money for the charity; they gave themselves a free party. And I knew that that’s not really how I want to operate. I came up with this idea that everyone would donate… everything.”

Since then, there’s been Cassoulet-Offs, Brisket-Offs, Soup-Offs, Chocolate-Offs, a better try at the Chili-Off. Just like at the Pie-Off I dove into, the Duck-Off contest entrants, both professional and home cook, brought it. But what really amazed me was how much they brought, sparing no expense on ingredients or portions, their enthusiasm for being part of the event seemed to feed their collective meters better than a sack of coins.

There was the Adrian Ashby, an amateur chef who made a fine-feathered dessert from strawberry compote, cannoli cream, Goslings rum, maple syrup, pecans, and duck butter. Crazy.

There was Nathalie Herling, a specialist in clay pot cooking, who made an incredibly intricate braised duck dish using ingredients only from the Americas.

There was Richard Pinto’s amazing rillette. There was Rachael Mamane, of Brooklyn Bouillon and Slow Food NYC, whose waste-not duck terrines were cleverly crafted from cooked down duck necks (28 of them!) and mixed with, among other ingredients in her silken-textured concoction, Cognac and Earl Grey tea-soaked prunes.

And then there was the winner, from Brooklyn chef Demian Repucci, whose sublime duck meatballs were the hit of the day.

The room was packed. Donated prizes were given to the gleeful winners. People ate and laughed and argued about whose food was best.

And Carbone? He just smiled.

“My whole philosophy now is there are so many resources that we have, whether it’s time or space or money or talent–so much can get done without money, you know? Whether it’s healthcare or food or whatever. There’s always an empty truck; there’s always someone with time…”

Jimmy Carbone Tells Chefs to Duck Off: http://tinyurl.com/3rjd93x