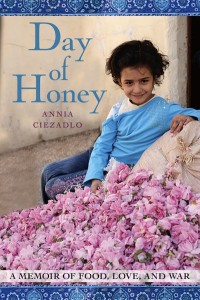

No question that food is the pulse point of our universe, not just in sustaining life but in some cases, in making life worth living. In her new book, Day of Honey: A Memoir of Food, Love and War, Annia Ciezadlo describes her years as a bride and a journalist in places most of us see only on CNN: Beirut and Baghdad, during the dark, troubled post-9/11 years.

Few authors have captured the true daily lives of regular people in 21st-century Middle East like this. Ciezadlo does in a way that not only tries to make sense of the senselessness of two countries rarely at peace, but also that lets us taste, literally, food that is put on the table so many miles away. In the words of Tevye in Fiddler on the Roof, these are people “trying to scratch out a simple, pleasant tune, without breaking (their) neck.”

Ciezadlo has some things to say about why she wrote this book. Most of these are prepared–but she kindly answered the last two questions that I sent her. So don’t stop reading until the end.

Q: What does “Day of Honey” mean?

It’s from an old Arabic saying that goes youm aasl, youm basl—day of honey, day of onions. People use it in a multitude of ways: sometimes to comfort each other, at other times ironically. It’s hopeful and cynical at the same time. One day might be sweet, the next bitter, but you keep going. You taste the honey while you can. For me, it sums up a wise, beleaguered optimism that the Palestinian writer Emile Habiby called pessoptimism: that no matter how bad things get, you don’t lose your faith in human nature. Or your deep conviction that something disastrous is just about to happen.

Q. You covered wars, assassinations, uprisings, and Middle Eastern politics for outlets like The New Republic and The Christian Science Monitor. Why switch gears and write about food?

I don’t think there’s a difference between writing about food and writing about war or politics. Food is inherently political: Who makes it? Who buys it? Who eats it, and who doesn’t, and why? All of these are deeply political questions. Follow them and they lead you to power, economics, inequality, and even war. So you could say that I am still writing about politics. Just in a more concrete form than before.

Food is part of war. I covered wars and conflict in the Middle East, and plenty of politics, but the stories I found most fascinating were the dramas of everyday life. How do families in a war zone send their kids to school? Drive to work? Make dinner every night? I found that people took comfort in small, everyday routines—the kind of domestic rituals we might take for granted, or even resent, in a country at peace. One of those rituals was cooking and eating. People can find tremendous comfort in food during wartime, especially when they can eat it together. It’s calming, especially if you’re making comfort food. It’s something you can share with others. And when your life is turned upside down, a meal can capture the essence—the flavor, the fragrance—of the ordinary life that you’ve lost.

Q. As a journalist, you’re used to telling other people’s stories. How did it feel to tell your own story? Was it an easy switch to make?

I’m always more interested in other people’s stories than my own. But with Day of Honey I realized that I had to tell my own story in order to talk about the people in whose lives I shared in Beirut and Baghdad. Telling my own story was a way to introduce their stories and points of view in a way that seemed more natural, and more honest, than pretending to be a fly on the wall. And that’s another reason I chose to write about food. As an American woman married to a Lebanese man, I had access to a world of families and domestic life that most foreigners never get to see, and food was a window into that world.

When your life is turned upside down, a meal can capture the essence—the flavor, the fragrance—of the ordinary life that you’ve lost.

In countries like Iraq and Syria, with long histories of government surveillance and control, people are very cautious about what they say. They’re not going to reveal what they really think to an outsider. They’re going to give them the pre-approved soundbite—either “Death to America” or “we love America,” depending on who their political leaders are aligned with. Even in Lebanon, which is more liberal in some ways, people are often careful what they say to outsiders. But because I was part of the family, literally or figuratively, people would say things to me that they would never say to another foreign journalist, no matter how persistent. And often the most revealing conversations would take place around the dinner table. When you’re eating together, with family or close friends, people don’t speak in soundbites. I was able to hear what people really thought. At the same time, I had the ability to step back and analyze that as an observer. (I speak a little Arabic, which helps a lot.) I had the unique privilege of being able to see this world as an insider and an outsider at the same time, and writing about these meals was a way of letting readers get a glimpse of this unseen world.

Q: Why did you weave history, politics, and literature into your story?

This is probably thanks to my background as a journalist, where it’s normal do about ten times more research and reporting than what you actually end up putting in your story. The history and politics in the book are only a fraction of the research I did. In addition to the hundreds of people I interviewed in my years in the Middle East, I also spent three years researching food and Middle Eastern history. I read books about the topography of medieval Baghdad, classical Arabic food poetry, and ancient Mesopotamian beer. I went on a history bender. I read a history of salt (by the magnificently obsessive Mark Kurlansky) and a history of sugar (Sidney Mintz’s brilliant Sweetness and Power). A lot of these books are included in the bibliography; if you want to geek out on Middle Eastern food and history, it’s a good place to start.

Q: How did you decide what to include and what to leave out?

One of the hardest skills for a writer is knowing what to leave out. I would have loved to include characters like al-Jahiz, for example, a medieval Iraqi writer and book lover who wrote an entire book about wine. But a friend of mine put it brilliantly: when you make a stew, you put in a bay leaf. The flavor of the leaf will infuse the stew, but you don’t actually eat the bay leaf itself, because it’s too hard and bitter. So all this history and research informs Day of Honey, and the flavor is there, but I took out the woody stuff to make it edible.

Q: What was your favorite thing about living in the Middle East and learning about the food?

Reading the oldest written recipes in the world, which are from ancient Mesopotamia (now modern-day Iraq), and realizing that they have a lot in common with the foods I was cooking and eating with people in Iraq and Lebanon today. It was such a thrill to read these 3,600-year-old recipes and see them not just as history, but as the beginnings of a culinary tradition that ended up in the bowl of soup I was eating that day.

Q. What surprised you most about Beirut and Baghdad? How did your view of the Middle East change after living there for over six years?

We get most of our images of the Middle East from wars. A bomb goes off, the television crews go film it, and we see people jumping up and down and shouting and waving their fists. If you watch a lot of TV news, you’d be forgiven for thinking that everyone in the Middle East gets up in the morning, drinks a cup of coffee, and goes outside and shouts “Death to America!” until it’s time to go to bed and do it all over again. No wonder we think they hate us.

But most of the ordinary people I met, with a few exceptions, didn’t hate Americans. Quite the reverse—they would often ask me, with genuine puzzlement, why we hated them. It was such a perfect reversal of the stereotype that sometimes I almost had to laugh. Many people in the Middle East are deeply angry about U.S. foreign policy. But almost everyone I met in Baghdad, Damascus, or Beirut—with a few notable exceptions—made the crucial distinction between our country’s government and its people. That’s a distinction we don’t always make with them. But we should. And that’s why I focused on the ordinary people whose voices are often drowned out by militants or demagogues.

Q. Did you have culture shock on moving to the Middle East?

Baghdad was a fascinating place because it was frozen in time—under Saddam Hussein, it was cut off from the rest of the world for decades. After the American invasion, it was opened up to the rest of the world, and in a sense everyone in Iraq had culture shock. Beirut is different. It’s wordly, sophisticated, and yet traditional at the same time. In Beirut, my friends would always warn me not to be taken in by the city’s cosmopolitanism. For example, I would often be surprised to hear young people with college degrees, who were intelligent and well-traveled, and otherwise liberal, speak against interfaith marriage. And I heard this from both Christians and Muslims.

One of the hardest things was reminding myself that even though people might look familiar, sound familiar, and eat grape leaves that taste like my grandmother’s, they had completely different histories and associations than mine. People all over the world want the same things: to grow up, get an education, get married and have kids and give them a good life. But they want them in different ways. I might not agree with a Muslim woman who wants Islamic law, or a Christian man who’s opposed to interfaith marriage. But I think it’s important to understand why they might want these things, and that it doesn’t necessarily make them bad people.

Q. What was it like being an American woman in the Middle East?

People ask me that a lot. I’d like to say that I struggled terribly, but the truth is that, for a reporter, being female was actually a tremendous competitive advantage. People find you less threatening. They’re quicker to let their guard down and reveal what they really think. They’re more likely to invite you into their homes and introduce you to their families. Being female gives you incredible access to that unseen world of private life that most Americans never glimpse. When was the last time you read a substantial article about Iraqi women’s political rights? Or a long magazine profile about someone like Dr. Salama al-Khafaji—and trust me, the Middle East is full of women as remarkable as her? I see them as the real story, and I think a lot of Americans want to read that untold story. Which is why I wrote this book.

Q: How did you decide what recipes to include? Why didn’t you include typically Middle Eastern dishes like hummus and tabbouleh?

I chose the recipes for Day of Honey very carefully. I decided that I would only include recipes that were part of the story of the book—like mjadara hamra, the lentil and wheat dish that my mother-in-law made before my husband and I left Beirut for Baghdad in 2003. The meals are part of the narrative, and I wanted the recipes to reflect that by giving readers a chance to eat a piece of the story. Each recipe becomes a story in itself.

There’s another reason. In the book I write about the difference between restaurant food and home cooking. Restaurants are more likely to serve meze—the small plates, the social foods of the Mediterranean, which include hummus and tabbouleh. So people are more familiar with them, and cookbooks and food blogs are more likely to include them. But there’s an entire universe of home-cooked meals that most Americans never see, and many cookbooks don’t have recipes for them. Home cooking is a metaphor for that hidden private life of the Middle East, and I wanted to give readers a taste of that world.

Q: If you were charged with finding ways to make the exchange and sharing of meals, recipes and food a strategic peacemaking tool in the role of a formal cabinet member or ambassadorship, how might you do it?

I would require each ambassador or cabinet member to spend two weeks preparing and serving meals for average-income families. They would have to follow the families’ budgets, and cook in their kitchens. If politicians don’t understand how average people live, how can they address things like war and peace?

Q: How has this experience, these years in Iraq and Lebanon, changed you and influenced the way you approach food and cooking now?

I used to feel like I wasn’t really cooking unless I added a dozen rare ingredients and made them all change color, shape, and size at least once. I learned two lessons in Beirut and Baghdad: first, I found out what it was like to live without constant access to things we take for granted, like fresh vegetables or milk. I met people who didn’t have reliable running water, or electricity, or real stoves. And I saw them make astounding meals from a handful of ingredients—sometimes literally making a feast out of weeds. These things taught me to bring some intellectual humility into the kitchen. They taught me to appreciate fresh fruit and vegetables when I have them, and good meat, and clean water. Nowadays I try not to gild the lily by overcooking and overspicing. I try to step back and ask myself: what is the simplest thing I can make with this lettuce, these fresh eggs, that bunch of green garlic?

Leave a Reply