Spiced cranberry. Licorice nectarine. Pear. Mexican chocolate.

No, these aren’t the eclectic delights of a particularly creative ice cream parlor, or perhaps the fantastical names given to nail polish or lipstick.  They are the flavors of artisanal bitters, and they’re coming to a cocktail near you.

They are the flavors of artisanal bitters, and they’re coming to a cocktail near you.

“Bitters are really a seasoning for cocktails; a way to add depth and a dynamic element to your drink that it might not have had on its own. They’re a varying and flavoring agent,” says Miles Thomas, a bartender and the owner of Scrappy’s Bitters in Seattle, WA. “The bittering part acts like acid in cooking and helps brighten up flavors.

“It sort of does the opposite of what people think,” he continues. “When you add bitterness to a drink, it really smooths it out and makes it a little bit easier on the palate. Some bartenders figured that out back in the day when there were a lot of spirits out there that were immature, unaged, or inexpensive. They figured, ‘Hey, if we add some of this we can add some of that depth, complexity, and roundness here without spending a ton of money.’ It was a way to create something delicious that was inexpensive.”

Old-School Bittermaking

Today, the movement toward house-made and carefully crafted product isn’t by any means cheap, but it has blossomed like bushels of summer herbs with bartenders all over the globe, who have utterly changed the face of cocktail culture from prefabricated, sticky-sweet concoctions to drinks with provenance. Much of this has been not only due to creativity and a more culinary,loca-pourstance on mixology, but also from resurrecting pre-Prohibition-era spirits, tinctures, recipes, and craftsmanship—in which bitters played a pivotal role.

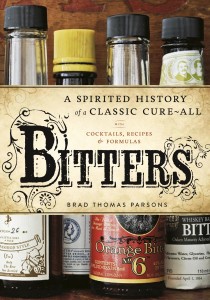

“In bitters heyday, there were dozens of brands. Any reputable bar made its own house bitters to administer. There were the classic aromatic, root-based versions, but celery and orange were staples as well,” says Brad Thomas Parsons, author of the soon to be released Bitters: A Spirited History of a Classic Cure-All (November 2011, Ten Speed Press).

“In bitters heyday, there were dozens of brands. Any reputable bar made its own house bitters to administer. There were the classic aromatic, root-based versions, but celery and orange were staples as well,” says Brad Thomas Parsons, author of the soon to be released Bitters: A Spirited History of a Classic Cure-All (November 2011, Ten Speed Press).

And, indeed, they were often used to cure what ails you—in Sweden, Italy, and France; in South America; and in the horticultural teachings of Native Americans to the pilgrims, herbs and roots distilled into a potable elixir was thought to cure everything from a bad stomach to a headache.

“When you add bitterness to a drink, it really smooths it out and makes it a little bit easier on the palate.”

“Strong digestion is the cornerstone of good health, and most traditional cultures around the world have long used bitter herbs to aid this,” says Jovial King, an herbalist and the owner of two-year-old Urban Moonshine, an organic bitters company in Burlington, VT. King produces three flavors (citrus, maple, and the root-based original) using herbs sourced mostly from local organic farmers in Vermont and upstate New York, and has plans to roll out several new versions specifically for the bar trade this year.

It may well have been that medicinal background that saved bitters from falling into utter imbibable extinction. “During Prohibition, the craft of cocktail was devastated, and it was the deathblow for bitters,” says Parsons. A couple versions survived the post-Prohibition, insta-cocktail decades that followed—Angostura from Trinidad, and the New Orlean’s made Peychaud; other once popular potions, like Abbott’s, didn’t.

Orange bitters, an important ingredient in many classic drinks, were resurrected by bar guru Gary Regan, who began to produce his own in the 1990s. But in the late twentieth century and early twenty-first, as people began to look more closely at the source of their meals and the ingredients that went in them, the same happened for drinks as well—it was only logical that bitters would follow suit.

Trending Bitters

Today, new companies seem to be popping up everywhere you turn, like seasonally minded A.B. Smeby Bittering Company, who hand crafts flavors like Highland Heather and Cherry Vanilla, with ingredients sourced mostly from New York-state farmers, Bittermans who uses mostly organic ingredients for exotics like Xocolatl Mole bitters, and upstarts like Thomas and his Scrappy Bitters, who began making them along with other tinctures and infusions while working at Seattle’s Serafina. Thomas’s two-year-old company, which gets its title for his nickname earned during a brief boxing career, are made from entirely organic herbs, roots, and citrus fruits sourced in large part from Mountain Rose in Oregon (who also sell their products retail online, if you fancy trying to make your own).

“Someone gave me a little recipe for orange bitters, and at that point, there were no other bitters around except Regan’s, Peychaud, and Angostura. I made it and thought, eh, this is all right, but I can make it better from what I’ve learned. I got into herbs and spent pretty much all my money buying them, learning about them, and just went crazy with it.”

Thomas started with about 50 bottles and sold out in a day. Today, he produces 7 purely organic versions—lavender, celery, chocolate, orange, grapefruit, celery, cardamom, and lime—and is up to a 3,000-bottle production. “I really think it was because I was using fresh and natural ingredients. That was why I also realized, when I was making infusions, syrups, and vermouth, that when you make it yourself you don’t spare expenses; you don’t say what’s the cheapest, crappiest orange I can find to make bitters, or use powdered orange. I thought, I can use better ingredients and make a better product.”

And so from bitter comes the better.

[Thanks, Amy–great talking bitters with you!] ] RT @AmyZeats RT @toquemag: Better #Bitters http://t.co/JYwAugd @ScrappysBitters @BTParsons