If Lisa Laird could climb upon the shoulders of the nine generations–and 230 or so years–of Lairds before her in Scobeyville, New Jersey, she could likely see all the way to Scotland where her great-great-great-great-great-great-great-grandfather, William Laird, hailed and hauled off for a different life in the New World in 1678. But as the ninth generation to head up Laird & Company, distillers of American apple brandy—aka applejack–and the oldest commercially operating distillery in America, she’s a little more interested in looking forward than looking back these days.

If Lisa Laird could climb upon the shoulders of the nine generations–and 230 or so years–of Lairds before her in Scobeyville, New Jersey, she could likely see all the way to Scotland where her great-great-great-great-great-great-great-grandfather, William Laird, hailed and hauled off for a different life in the New World in 1678. But as the ninth generation to head up Laird & Company, distillers of American apple brandy—aka applejack–and the oldest commercially operating distillery in America, she’s a little more interested in looking forward than looking back these days.

Still, Laird’s history is undeniably cool, and certainly worth revisiting–especially when you take a look at how much the Garden State’s gardens have dwindled: According to the New Jersey chapter of the Sierra Club, as recent as 1950 there were over 2 million acres of fertile farmland here; today, it’s shriveled to about a quarter of that. But back in the day (the 18th century day, that is) apples were almost as good as gold.

“When I did some research on advertisements for farms for sale in the 1700s in our area, all but one of 20 of them mention that, as a plus, the property had orchards,” says David Blackwell, President of the Hopewell Valley Historical Society in Hopewell, New Jersey. “It’s my understanding that the small farms of Bergen and Essex Counties were in some cases devoted wholly to apples for a cash crop, and Newark cider and apple whiskey had an international reputation.” New Jersey apples were so renowned, even gentleman farmer Thomas Jefferson was known to purchase them.

But neither dwindling orchard land nor Prohibition nor the vodka-swilling 80s and 90s could keep the Lairds from their family calling; one that’s seeing a bit of a renaissance these days. Here, Toque talks apples, the rebirth of the Jack Rose, and why applejack kicks Calvados’ butt with current Vice President of this historic applejack producer, Lisa Laird Dunn.

Distilling in America is certainly as old or older as the country itself – where does Laird fall into the timeline?

My original ancestors came over in 1678 from Scotland. They arrived here in the area we are now, in Monmouth County [New Jersey] in 1698.

So it’s not a stretch to think they may have been whiskey distillers in Scotland.

The assumption certainly is that they were distillers in Scotland, and then they found apples here and started distilling from them. It started off for personal consumption and bartering. We had our own general store in town and we were proprietors of the Colt’s Neck Inn. Our first on-the-record sale isn’t in the books until 1780 from Robert Laird, but the family was producing prior to that.

Was there a lot of competition?

You know, everyone made their own applejack. It was especially popular anywhere where apples were abundant, and people would make their own during the Revolutionary times and Colonial days. A lot of property then was valued at a higher price by the number of cider apple-bearing trees. They’d even put that in the listing when they were selling property. Apples in this area, especially Monmouth County, were big.

Did you stop producing during Prohibition?

We did stop producing here. We were still producing cider and non-alcoholic products, but there was a lot of bootlegging going on in the area. We were given a federal permit to produce for medicinal purposes during Prohibition, though, so we had that advantage. Once Prohibition was lifted, we had a supply of apple brandy immediately available to the market.

What changed for Laird’s post-Prohibition?

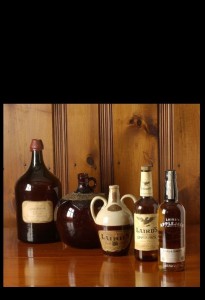

After the alcohol ban was lifted, all these little bootleggers here in New Jersey decided to go into the legal business of selling applejack. Actually, my grandfather and my uncle had a campaign to save the integrity of it where they started purchasing a lot of these small distributors that made an inferior product. There were cases where people would take our empty bottles and refill them with another apple brandy and try to resell it as Laird’s. My grandfather actually had a patented non-refillable bottle developed, and that’s how we ensured the product was ours. It had a special metal cap on it that, once it was taken off, couldn’t be put back on.

What kind of apples do you use?

Winesap is most preferred, but we pretty much use any apples we can get today. There are not as many Winesap grown as there used to be. It’s not an everyday eating apple, but I think it’s one of the best you can have, although it’s not one of the prettiest looking. We also use Braeburns, Fujis, Red Delicious, Golden Delicious, and Pippin. We control the final product’s flavor by blending the different apples.

Kind of like Scotch?

Yeah, we try to control it to the best of our ability, but we’re only able to use what we can purchase. Once the brandy’s been distilled, we put it in once-used Bourbon barrels and keep an eye on it, basically taste-testing.

How is American apple brandy different from something like Calvados?

For one, the type of apples in our product. We use apples that you would normally eat every day. The cider apples they use in Calvados are very small, hard, tart apples – it’s not an apple you’d pick off a tree and enjoy eating. We are more regulated on the federal standard of identity with how we produce the product. In Calvados, what’s more regulated is where the apples are grown, like grapes are.

Before, no one was interested. It’s been the bartenders that have gotten us distribution in other countries. It’s amazing the influence they’ve had.

Also, they can add pear brandy to Calvados, and therefore most Calvados are not 100% apple brandy. We can only use 100% apple brandy; we cannot use any additives. And once we put our apple brandy in the barrel, we cannot add any fresh brandy as it evaporates and becomes the angel’s share. In Calvados, they can top off. We also can only use once-used Bourbon barrels to be called applejack. They can use Sherry, Port, new – any type of barrel to age it.

One last difference: I think ours is better.

How much do you make?

We produce 15,000 cases a year; we’re very small. It’s growing, though. We had slowed our production for quite a while, especially in the ‘80s when brown liquors were just shunned. It was all about vodka. So, obviously, we cut back because apple brandy is not a cheap product to produce–it’s 7,000 pounds of apples per barrel. It’s very costly to carry that inventory.

How has the current artisanal cocktail scene changed things for you?

The new enthusiasm for classic cocktails and classic ingredients has been a wonderful boon. Laird’s was available [pre-Prohibition] and was one of the original ingredients available for cocktails in America. So for bartenders who are looking for authentic ingredients and producing authentic cocktails, it’s been wonderful. People are reaching out to us from all over the world now.

If it weren’t for people like Audrey [Saunders] and mixologists like her, you still wouldn’t be able to find a lot of these products. They demanded it. But it’s still a constant battle.

We never used to export our products, but in the last four years we’re in the UK, Germany, Australia, and we are going to be starting in Sweden soon. Before, no one was interested. It’s been the bartenders that have gotten us distribution in other countries. It’s amazing the influence they’ve had. I’m forever grateful to the bartender community.

How many products do you make?

We have the blended applejack, which is 35% apple brandy and 65% neutral grain spirit, and the best way to describe that is it’s like a blended whisky, but it has an apple brandy base so it’s definitely a unique product. There’s nothing else like it. And then we have a straight apple brandy – our straight 100 proof, aka the Bonded, which is what’s been really embraced by the cocktail culture today. A lot of bartenders prefer to use it because it’s more like the original applejack from pre-Prohibition days. And then we have our 7 1/2 year old, which is aged a minimum of 7 1/2 years in barrels. And we also have our 12 year old–in 1999, we introduced that.

What are you most excited about for Laird’s these days?

That tending bar is a profession again and they take pride in what they’re doing and the product they’re offering to their customers. And that’s what it always was–it’s nice that it’s come back to that. The largest downfall of applejack was when the bar community moved away from fresh ingredients and started using things like that lemon-lime sour mix – it killed the Jack Rose. Killed it! It wasn’t the same drink. And now it’s like, wow! When you taste one today with fresh lemon juice and fresh homemade pomegranate syrup, it’s a whole different drink.

Lisa Laird Dunn’s Preferred Jack Rose

2 oz Laird’s Applejack

¾ oz freshly squeezed lemon juice

½ oz pomegranate grenadine (to make your own quick, homemade version, combine 1 cup pomegranate juice with 1 1/4 cups sugar and simmer until sugar dissolves; allow to cool before using)

Shake with ice. Then strain into a cocktail glass.

Applejack is baaack. And it's good. Laird's apple brandy and why it kicks Calvados' butt on Toque http://tinyurl.com/4rd9w7c